Post-Exertional Malaise (PEM)

PEM is the unique, identifying feature of ME/CFS.

It is also known as post-exertional neuroimmune exhaustion.

‘Malaise’– a vague feeling of discomfort or fatigue – is an inaccurate and inadequate word for the pathological low‐threshold fatigability and postexertional symptom flare.

'ME: International Consensus Criteria', Journal of Internal Medicine, 2011

Post-exertional malaise (PEM) or post-exertional neuroimmune exhaustion is a pathological loss of energy and worsening of all symptoms following minimal physical, mental or emotional effort, or other triggers. The onset of PEM may be immediate or delayed by several hours or days. Recovery is prolonged and may take days, weeks or months.

When people with ME/CFS push themselves to use more than their available energy reserves, the loss in functional capacity is inevitable and cannot be reversed simply by a long rest or a good night's sleep.

People often struggle to describe this loss of energy, weakness and exacerbation of symptoms. They may use words like 'crash', 'payback' or 'exhausted'.

Someone who is not familiar with the language of PEM may simply describe themselves as 'tired' or 'fatigued'.

There is sufficient evidence that PEM is a primary feature that helps distinguish ME/CFS from other conditions.

IOM Report, 2015, p86

Distinguishing characteristics of PEM

PEM can be distinguished from the post-exertional fatigue experienced in other fatiguing illnesses or in deconditioning by the following:

Delayed onset

The most commonly reported delay in onset of PEM following exertion or other trigger is one to two days, although some patients report a longer delay. Until individuals understand their own pattern of delayed onset, their fluctuating symptoms may seem confusing and unpredictable.

Under certain circumstances onset may be immediate, for example:

- when someone is already experiencing PEM and further exceeds their available energy limits

- in severe ME

- in very severe ME, where it may be triggered by barely discernible stimuli

Even when PEM is not delayed, it can be distinguished from post-exertional fatigue by the other characteristics of PEM.

All symptoms worsen

During PEM, all symptoms will increase, regardless of the type of trigger. The severity of symptom exacerbation is out of proportion to the intensity and duration of the trigger.

The increased symptom severity results in a loss of functional capacity.

... when I do any activity that goes beyond what I can do—I literally collapse—my body is in major pain, it hurts to lay in bed, it hurts to think, I can’t hardly talk—I can’t find the words, I feel my insides are at war...

Patient description of PEM, IOM Report, 2015, p78

Triggers

The triggers for PEM can vary widely between individuals. Even for the same person, the pattern of PEM can vary for different types of triggers and over the course of the illness.

The type, severity, and duration of symptoms may be unexpected and they are likely to seem extreme in relation to the initiating trigger.

Physical, cognitive and emotional exertion are all triggers. The amount of exertion that can be tolerated varies with the severity of the illness:

- mild – working, even part time, may prevent engagement in normal self-care and other activities of daily living (ADLs)

- moderate – while some activities are possible, even within self-care, judicious choices must be constantly made, e.g. a shower or a phone call

- severe – any self-care may be too much and precipitate PEM

- very severe – even basic bodily functions place too heavy a load on the body, and systems or organs may begin to shut down

Note that even for healthy people, the largest single component of energy expenditure is the energy the body needs to carry out basic metabolic functions (basal metabolic rate), such as breathing, circulation, etc.

Unlike post-exertional fatigue, PEM can be triggered by any provocation that places a demand on the body. In addition to exertion, this includes:

- sensory overload, including too much noise, light, vibration and movement

- postural changes

- weather conditions

- moulds

- volatile chemicals, including fragrances, cleaning products, paint and building materials

- infections

- medications, supplements and vaccinations

Prolonged recovery

Illness fluctuations caused by PEM may last hours, days, weeks, or even months. When the impact of a trigger is severe enough, PEM may lead to long-term deterioration, with a worsening of illness severity.

Underlying abnormalities

Studies suggests that PEM is caused by abnormal energy metabolism, although the reason for this has not yet been clarified. Abnormal gene expression and immune biomarkers following physical exertion have been described, but the situation is very complex and more research is needed.

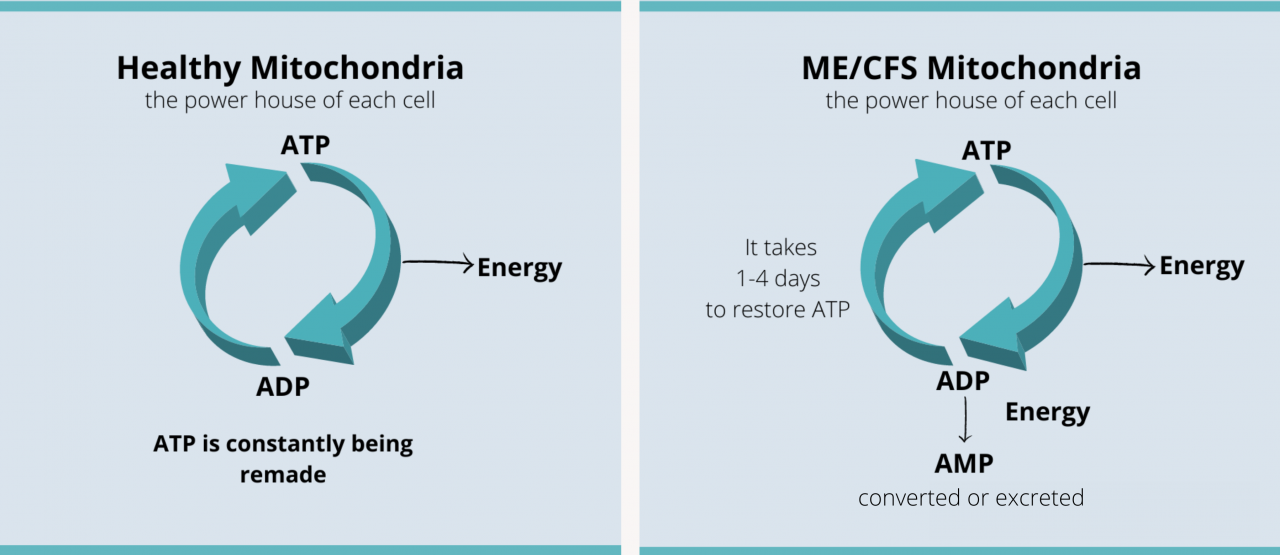

In the mitochondria of healthy cells, ATP (adenosine triphosphate) is the main source of energy, as demonstrated in this short animation. When ATP is broken down to ADP (adenosine diphosphate), energy is released. ADP is then converted back to ATP under normal aerobic conditions (i.e. in the presence of sufficient oxygen). During high levels of intense exertion, cells switch to oxygen-independent (anaerobic) energy production. This is less efficient and produces unwanted by-products.

In ME/CFS, studies have indicated a problem with energy metabolism, causing patients to switch from aerobic to anaerobic energy production at much briefer and lower levels of exertion than healthy people and to recover from its adverse effects more slowly. Reduced ATP reserves and reduced ATP synthesis have been reported, along with increased production of products of anaerobic metabolism, such as lactate.

In very simplified terms, one possible difference between the ATP cycle in healthy people and those with ME/CFS may be something like the following:

It has been suggested that in ME/CFS replenishing ATP levels can take days, which may contribute to the prolonged symptoms and functional deficits associated with PEM.

In patients with ME/CFS, aerobic metabolism may be impaired. Thus, any physical exertion exceeding 90 seconds may utilise a dysfunctional aerobic system...

ME/CFS: A Primer for Clinical Practitioners, IACFS/ME, 2014, p14

Assessment

Identifying PEM is an important step in the diagnosis of ME/CFS. A detailed clinical history is needed to identify the delayed onset, worsening of all symptoms, triggers, and prolonged recovery time.

Symptom reporting may be complicated by:

- poor understanding of PEM by the person with ME/CFS

- infrequent experiences of PEM in people who successfully manage their energy expenditure

It may be useful to keep a diary of triggers, including activities, and noting changes in symptoms.

PEM can be objectively assessed using the two-day cardiopulmonary exercise test (CPET) in people who are well enough to undertake it. In ME/CFS, the physical exertion involved causes reduced function on the second day of testing. However, the test may worsen a person’s symptoms and even cause a long-term relapse.

PEM can also be assessed using validated questionnaires from DePaul University. The first questionnaire is a short form to indicate the presence or absence of PEM. The second questionnaire explores the nature of the individual's experience of PEM.

- DePaul Symptom Questionnaire – Post-Exertional Malaise:

DSQ-PEM– PDF & Scoring Guide - DePaul Post-Exertional Malaise Questionnaire:

DPEMQ – PDF

Management

The primary goal of management is to avoid PEM.

Identifying and avoiding triggers

Triggers for PEM vary between individuals and over time in the same individual. The more severe the illness, the less the stressor needed to trigger PEM.

The impact of triggers is cumulative; the total load influences PEM.

A symptom diary that incorporates a record of potential triggers may assist in identifying causes of worsening symptoms. If possible, these triggers should be avoided. When a specific trigger is unavoidable, care should be taken to reduce exposure to other potential causes of PEM.

A raised heart rate can be a helpful indicator of exertion that is exceeding the body's available energy capacity. Information provided by a heart rate monitor may allow identification of triggering activities or experiences. Modifying, reducing or avoiding these activities will reduce the likelihood of PEM.

Pacing

Pacing is a strategy for avoiding PEM, by managing rest and activity so that not all available energy reserves are expended.

Resting to aid recovery from PEM

Replenishing the depleted supply of energy will generally occur more quickly if demands on the body are minimised, by lying down and reducing sensory input. Note that this may not be experienced as restful, due to a heightened awareness of the worsened symptoms.

Learn more about PEM

- Dialogues for ME/CFS includes two short videos on PEM, accompanied by links to educational materials and references.

- The NIH (US) held focus groups in order to better understand the lived experience of PEM. Their findings were published in September 2020. To read quotes from patients and to learn more about their findings, read their study.

Last edited: 18 January, 2024